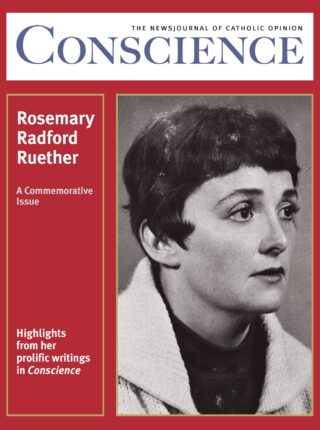

Remembering Rosemary Radford Ruether: Feminist Theologian for the Ages

Longtime Catholics for Choice board member, feminist theologian, and scholar-activist Dr. Rosemary Radford Ruether passed away on May 21st, 2022. Mary E. Hunt, feminist theologian and co-founder of Women’s Alliance for Theology, Ethics, and Ritual (WATER), remembers Radford Ruether’s life in this obituary.

Rosemary Radford Ruether (1936-2022) graced Catholics for Choice circles for more than three decades, most of that time as an active board member. She was a world-class theologian whose academic work enlightened minds, changed hearts, and sustained strategies for ecclesial and social change. At the same time, she was a beloved colleague — reliable, steady, humorous, uninterested in the petty stuff, and always on the moral mark.

Reams will be written about Rosemary in the decades to come. It is impossible to overstate her role in Catholic efforts to bring about effective, accessible, economical birth control and abortion. We are in her debt for clarity and courage.

Rosemary was raised as a critical Catholic by a mother who taught her to separate the Catholic wheat from the chaff. The Radford women paid attention to the Catholic things that made for peace and justice, as well as to the spiritual and aesthetic riches, and left the rest aside. Rosemary maintained that it was a big community of a billion people worldwide with whom she felt connected, not a small cohort of clergy who presumed to speak for all. She said that she was the fly on the back of the Catholic horse because it was her horse.

Rosemary’s early thoughtful inquiries of priests led her to her vocation. In a 1993 issue of The Christian Century, she wrote, “When I pursued intellectual conversations with Catholic priests (including an 18-month correspondence with Thomas Merton between August 1966 and December 1967) I ended up feeling that I was mentoring them, rather than the reverse. It was a long time before I met any Catholic theologians who I felt had really worked out the kind of unified intellectual and spiritual authenticity I sought. I realized that I would have to work it out for myself. So I became a theologian.”

Rosemary told one story about her young daughter playing, looking at book after book. The child’s grandmother asked what she was doing. The little girl said, “Playing Mommy,” spoken like a child of a mother who dealt with original languages and translations.

Catholic women theologians of Rosemary’s generation did not have an easy time. Most “great theologians” of her cohort were white male priests, but Rosemary did her work without a whit of clerical privilege. Male theologians had living stipends and educational funding. They had housekeepers and a rectory in which to live. A priestly salary was normative for male theologians and unheard of for Catholic women. Rosemary, her husband, Herman Ruether, and their three children lacked the denominational support that is a hidden resource for many colleagues in the field of religion.

Rosemary Radford Ruether wrote for Conscience all the time.

To read some of her best articles, check out our 2011 commemorative Conscience issue.

Read now!When Rosemary confronted her own reproductive years with three children under the age of 7, it was a no-brainer to reject “Humanae Vitae” (“Of Human Life”) despite the wrath of clerical church leaders. She lost her first teaching job at Immaculate Heart College because local church authorities pressured the nuns against rehiring a scholar who had the temerity, courage, and intelligence to reject the institutional church’s teachings on sexuality.

When Catholic conversation turned to abortion, it was no surprise that some Catholic women theologians, including Rosemary, once again stood with their sisters. Rosemary knew the tradition on abortion: Most Jewish teaching was that life began at birth while Catholic teaching varied with quibbles over when ensoulment or personhood began. Unlike the institutional church’s theological method, an endless recycling of prior church teachings, Rosemary’s method included both scientific data and women’s experiences as important elements of analysis.

She understood that conception was a biological process rather than a magic moment, and that pregnant people were the most affected — and therefore had the moral right to decide whether to carry a pregnancy to term.

Rosemary lived in a world that was far more than Catholic and far more than sexual. It was interreligious and secular; it was economic, political, racial, and ecological. Thus, she developed her Catholic pro-choice position in a pluralistic world in which women’s reproductive choices, like everything else, were conditioned by macro structures of oppression and privilege that need to be realigned.

She framed her affirmation of abortion in the context of real circumstances in real women’s lives, rejecting the institutional Catholic church’s reductive fetishes about fetuses. She took abortion seriously as a weighty moral matter and also took women’s moral agency as a given.

Rosemary paid a price for being pro-choice. It did not stop her from continuing her scholarship and advocacy. In 2008, the University of San Diego offered — and then quickly withdrew — to Rosemary a chair in Roman Catholic Theology. It was widely reported that her membership on the board of CFC was a primary reason for their decision. Rosemary never wasted time on such trivial snubs, but her colleagues mounted a letter campaign to no avail and to the lasting shame of the University of San Diego, which has never had her equal on their faculty.

Despite the seriousness of her work, Rosemary always seemed to have a great time. Sitting next to her at a meeting meant being entertained by some of her drawings; art was her second choice as a field of study. Her humor came out in such hilarious titles for papers as “St. Augustine’s Penis” and “Why Men Should Not Be Priests.” Rosemary’s insightful quips at the many human foibles she encountered were the stuff of legend.

Rosemary Radford Ruether was a singularly important theologian whose work will endure with the best of theology. Her genius was her ability to apply sophisticated intellectual research toward solving problems of daily life. She did it in ways that gave Catholic thought a good name — perhaps better than it deserved.

Great theologians are not always good people. Those of us who served with Rosemary can say that she was both. Our marvelous, modest colleague is now a feminist theologian for the ages. Deo gratias.