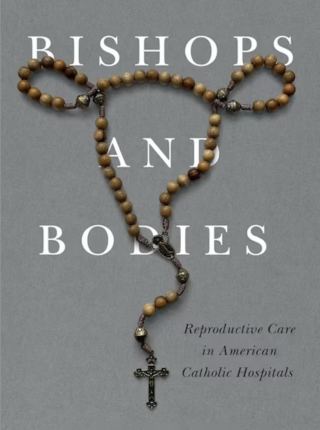

Book Review: Bishops and Bodies

Bishops and Bodies: Reproductive Care in American Catholic Hospitals

By Lori Freedman

Published by: Rutgers University Press

2023, 228 pages, $29.95

Shortly after the Supreme Court issued its opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, horrific stories began to emerge from hospitals across the country. Terrified of violating abortion bans that carried criminal sentences, doctors turned away pregnant patients experiencing medical emergencies — sending them across state lines or telling them they must wait to get sicker before they could receive treatment for an ongoing miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, or fetal anomaly. To many, these denials of emergency medical care seemed to be an alarming new consequence of the Supreme Court’s decision. Lori Freedman, however, has documented such stories for well over a decade. We would do well to study her work carefully — including her book Bishops and Bodies: Reproductive Care in American Catholic Hospitals — in this critical moment.

Bishops and Bodies is the culmination of Freedman’s extensive research into Catholic hospitals, which operate under a set of guidelines called the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care (ERDs). Authored by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, the ERDs prohibit doctors working in Catholic facilities — which occupy a large and growing share of the U.S. healthcare industry — from providing patients with routine reproductive health services including contraception, sterilization, abortion, certain infertility treatments, and care for gender transition. Freedman argues persuasively that these restrictions result in “doctrinal iatrogenesis,” a phrase she coined to refer to medical harm that is the result of religious ideology.

The stories of doctrinal iatrogenesis in Bishops and Bodies speak for themselves: a woman with multiple medical problems whose doctors scheduled her C-section a full two months before her due date to guarantee that she could receive a sterilization under bishop-imposed hospital rules, leaving her newborn in need of intensive care. A woman forced to listen to her fetus’ heartbeat for eight hours during a painful second trimester miscarriage before the heartbeat finally stopped and she was able to receive treatment. Women compelled to carry pregnancies to term even after learning their fetuses have fatal anomalies, such as acrania (the absence of a skull). Sexual assault victims denied emergency contraception because they had ovulated recently and therefore might already be pregnant — meaning that care is withheld from precisely those who need it most.

"An infusion of government funds has allowed Catholic systems to flourish without altering their religious policies."

— Elizabeth Reiner Platt

In addition to these gut-wrenching stories, Freedman regularly situates the ERDs in the larger context of American healthcare, showing how flaws in our medical and legal systems both allow and compound the harms of Catholic restrictions. For instance, because we lack universal health insurance, some patients find that that their insurance policies cover only Catholic hospitals. The sale of public hospitals to private religious institutions has added to the dearth of non-Catholic options for care, especially in rural communities. Broad protections for religious restrictions under federal law have stymied state efforts to ensure greater access to reproductive care. An infusion of government funds has allowed Catholic systems to flourish without altering their religious policies. And our capitalist approach to healthcare delivery has offered the illusion of choice, leaving patients blaming themselves for their own poor treatment for not having sought care elsewhere.

Freedman’s book opens the door to several questions without easy answers. What lessons from years of research into religious hospital policies are most relevant in our current moment, when doctors at religious and secular hospitals alike fear not just violating their hospital’s internal rules, but going to prison? What steps must we create to ensure an eventual return not merely to the pre-Dobbs days of reproductive healthcare that varied wildly based on patients’ race, class, and zip code, but to something better?

Perhaps the most significant question Freeman raises is how do we both recognize abortion as necessary healthcare for everyone and avoid pernicious narratives of “worthy” and “unworthy” abortions, while also acknowledging the specific horror of being turned away during a medical emergency — of being told you must wait until your life hangs in the balance to get treatment? Addressing this problem thoughtfully holds serious consequences, as the stigma of abortion and its removal from routine healthcare in both the medical community and the public eye offers a partial explanation for our current crisis.

Bishops and Bodies memorably demonstrates the power of abortion stigma through the stories of two Catholic women who objected not to receiving abortion care itself, but to the fact that the treatment they received for serious health complications was viewed as an “abortion.” In one instance, a woman who was treated for an ectopic pregnancy lamented that “the word abortion being used was just as traumatic as my loss.” A second patient, whose fetus was diagnosed with anencephaly, was able to convince a clergyman at a Catholic hospital to approve her abortion in the hospital after explaining that receiving care in an abortion clinic posed a threat to her religious identity.

While we have allowed ourselves to imagine abortion, and really all reproductive healthcare, as somehow distinct from other forms of medicine, Freedman shows this to be a mirage. Reproductive care is an essential part of treating patients who walk in the hospital door for everything from cancer to heart failure. As one doctor she interviewed explained, it would be impossible to simply remove reproductive healthcare from Catholic facilities — to accomplish this, “you have to never admit a woman to your hospital.”

So, with reproductive healthcare both indispensable and routinely denied, where does that leave us? As Freedman notes, patient education on religious healthcare restrictions may be helpful, but it is insufficient when no other source of care may be available. While many, as she explains, “urge individual solutions to large structural problems,” eliminating doctrinal iatrogenesis will require far more of us. It will require dramatic new approaches to how healthcare is conceptualized, regulated, and delivered. Furthermore, it will require a new understanding of religious liberty as a right that must protect first and foremost the ability of individual patients — not massive healthcare systems — to honor their own religious and moral values.